Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Alliance has been working with our NGOs to monitor the road safety response and how NGOs are adapting. The picture has certainly evolved over the past three months. Following initial shock and funding fears and faced with the significant task of moving as many activities as possible online, most are working around the lockdowns and curfews, and some have been able to return to business as (some kind of) normal.

As a global community, members are not all working under the same circumstances; in Europe and in Africa, countries are cautiously opening up, while Latin America is in the eye of the storm. NGOs in Asia share a mixed story of differing timetables and restrictions. In other ways, the issues faced are surprisingly similar: speeding, overstretched emergency staff, public transport, increased walking and cycling, and hygiene fears.

The biggest challenge that Alliance NGOs have faced globally has been how to push forward the road safety agenda when all attention is focused, quite understandably, on COVID-19. In particular, there is a fear that the gains and momentum of the Stockholm Declaration could be lost and that, the longer it takes to get back to normal, the harder it will be to regain the ground lost.

NGOs have respectfully waited on the sidelines until government officials have returned to their normal roles and until citizens are ready to hear their messages. They know that new energy is needed, in particular for the Stockholm Declaration, which sets out a road map for road safety for the next 10 years. But when and how can this be achieved, and what messages will people be ready to hear?

In a series of calls held in the second week of June, Alliance member NGOs debated these questions. They found:

WHEN is very country- and even region-specific and related not just to the speed at which a country is reopening but also to socioeconomic factors and how open the government is to safety messages. In some countries, notably in francophone Africa and Europe, there is a sense of urgency, knowing that governments are ready to talk and the issues must be faced now.

In others, particularly in parts of Asia, the point at which road safety can be brought back to the agenda is still a long way away, the fall or beyond, due to fears of a second wave of the virus.

NGOs differentiated between advocacy with government and advocacy with citizens. Government is active, they reason, and some of the issues that are arising—such as safety on public transport, walking and cycling, and speeding—are urgent. Some governments, such as Nepal’s, are actively engaging with the road safety agenda right now, and these opportunities must not be lost. Around the world, in high-, low-, and middle-income countries, the need is being seen for policies and implementations that protect and encourage walking and cycling. The time for this advocacy is now, before the moment is lost.

On the other hand, many NGOs felt that campaigns targeting citizens were further away, that people are still more concerned with the effect of COVID-19 on their lives than the multitude of other concerns that affect our daily lives.

WHAT specific road safety agenda we should be pushing is always difficult to determine among a global cohort of local NGOs. While some issues are always common across all countries—speed, the target to reduce road deaths and injuries by 50%, safe systems—some are specific to particular regions— such as moto-taxis and the problem of shared helmets, and children on motorcycles.

Certain themes, however, carried strongly through the discussions, in particular the concept of building back better, connecting road safety to sustainable mobility, planning, and climate change. It was strongly felt that road safety advocacy would be better received in the short term if it was linked to COVID-19 concerns—hygiene, social-distancing, public transport, health systems, and sustainable mobility—tapping into fears but also hopes for a better future for citizens after the pandemic.

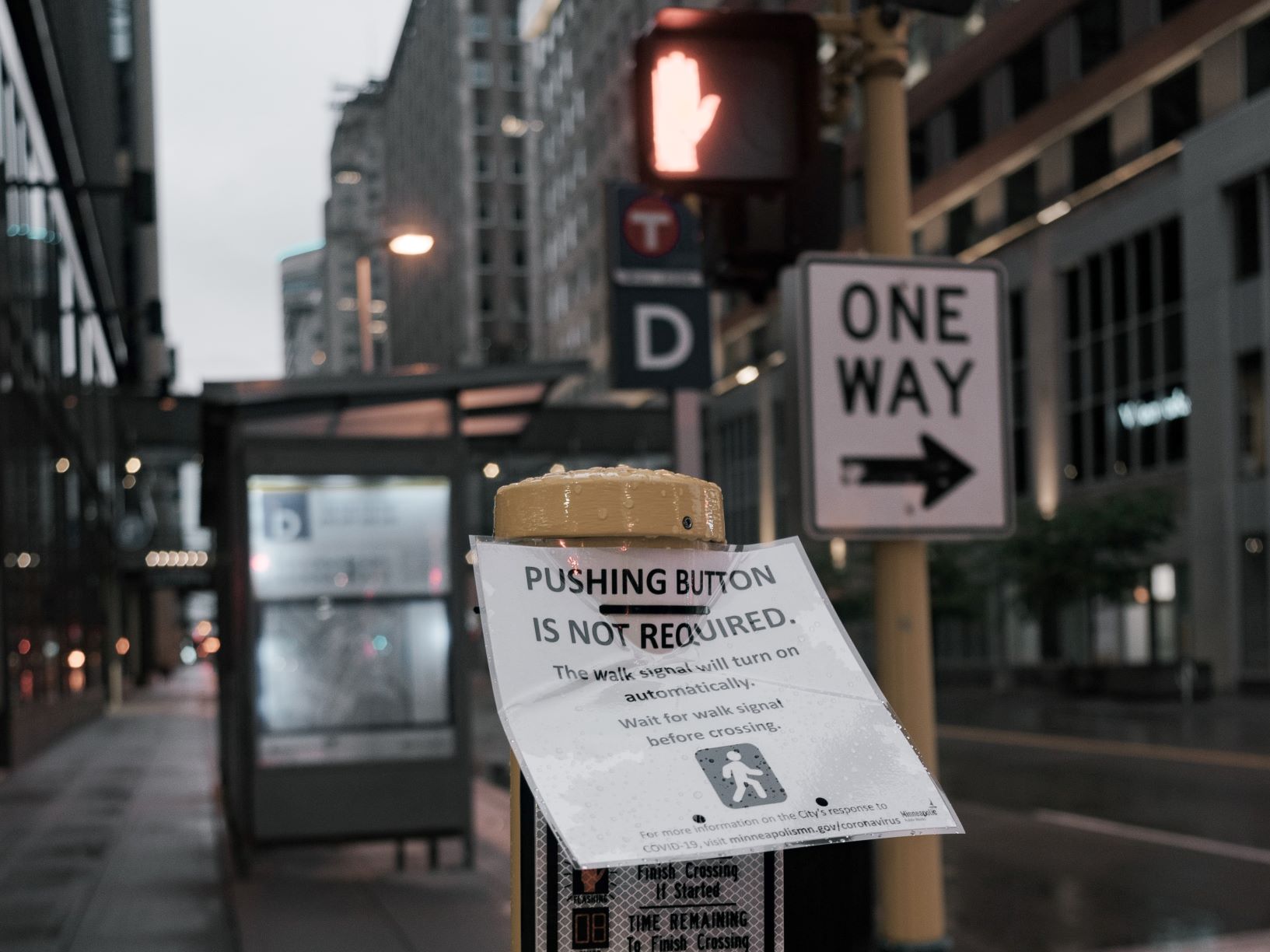

Across the world, in low-income countries as well as high, there has been an increased interest in cycling and walking as a result of lockdown restrictions. Many cities have responded by implementing temporary cycle lanes and walking streets. These active forms of transport tick many boxes: they are cleaner, more sustainable, healthier, better for cities, more equitable, and, if the correct policies and infrastructure are in place, safe. Interestingly, the Stockholm Declaration taps into these very same issues. While the effects of the pandemic could not have been anticipated, the Declaration rings even more true in the light of the current debates around clean air and mobility.

Trust needs to be rebuilt in public transport. Many people are afraid to take public transport at the moment, and there is a danger that private car usage will increase (for those who can afford it), making roads less safe for walkers and cyclists, increasing pollution, and exacerbating inequality.

A particular area of concern was noted around children and school journeys. How can NGOs support safe travel to school and back when parents are afraid of public transport and may or may not have access to a private car? Will roads become more congested? Will parents keep their children at home?

HOW to bring attention to safer roads and mobility was perhaps the hardest issue. Some NGOs have found opportunities with their governments; a few have been able to restart community activities, but more are still operating mainly online.

Clearly, a coordinated NGO campaign must look a bit different from normal: no crowded events and training workshops. Online will play a bit part, but campaigns in different parts of the world may look very different.

More than ever, road safety NGOs need to be ready and active, offering their support to overwhelmed local and national governments and helping them to do the right thing.

Read the full notes from the sessions HERE.