* Grade-separated crossings should only be used as a last option.[2] According to studies, many pedestrians will not use grade-separated crossings if they can cross at street level in roughly the same amount of time without walking considerably further.[3] Grade-separated pedestrian crossings are expensive in comparison to other crossing solutions.[4] Furthermore, they allow motorists to drive at higher speeds. They are most feasible and appropriate in cases where pedestrians must cross high-speed, high-volume roads such as freeways and arterials[5] or where a large number of pedestrians will benefit.[6]

Areas where pedestrians need to cross or walk along the road. In practice, this would include residential areas, villages, markets, retirement villages, school zones, healthcare and hospital precincts, around places of worship, university hubs, public transport hubs and major train station zones, city centers, and central business districts (CBD).

and/or

Areas where deaths or serious injuries occur from road crashes among pedestrians.

The Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030 (Global Plan)[7] sets a target to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030. Achieving this target requires implementation of evidence-based interventions that are known to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries. Pedestrian facilities are one such evidence-based intervention.

Globally pedestrians represent 23% of all traffic related deaths.[8]

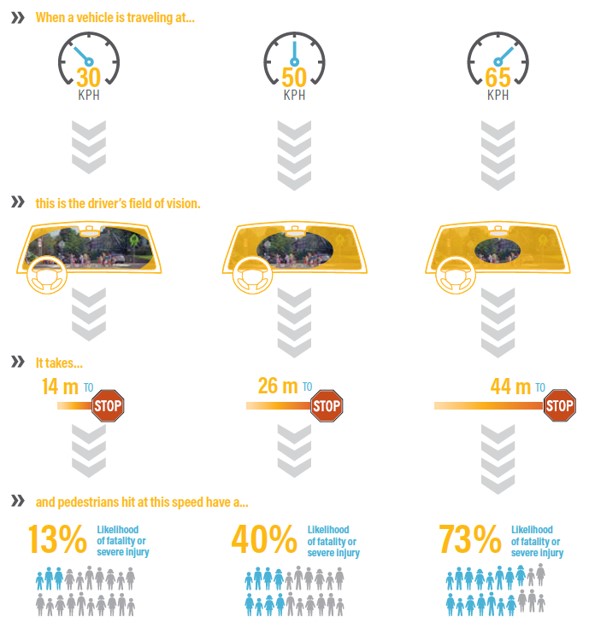

There is a 73% chance of a pedestrian dying if hit by a car traveling at 65 km/h and a 40% chance of dying at 50 km/h, as opposed to a 13% chance at 30 km/h (Figure 1).[9]

The higher a vehicle’s travel speed, the more difficult it is for the driver to predict or detect potential conflicts on the road due to reduced levels of peripheral awareness[10] and the longer it takes for the vehicle to stop (Figure 1). This increases the probability that the vehicle will hit a pedestrian and that the pedestrian is severely injured or killed.

Intersections are particularly dangerous for pedestrians as they include a large number of pedestrian-vehicle conflict points. Uncontrolled intersections (intersections without signs or traffic lights to indicate the right of way) worsen the situation, as pedestrians may face oncoming vehicles traveling at high speeds that are not required to stop or yield.[13]

Pedestrians are often not provided with a safe and frequent crossing point or given the right of way. This means that they are left to signal their intent to cross by standing in the roadway, thereby increasing their exposure to a potential collision, which may result in death or injury.[14]

While signalized intersections are generally safer than uncontrolled intersections, pedestrians still face potential dangers. For example, drivers do not give the right of way to pedestrians and start turning while pedestrians are still crossing or before they start crossing. Pedestrians may also be obscured from the driver’s line of sight. Finally, allocated crossing times may not be long enough for some users and/or the width of the road to be crossed.

If it takes a pedestrian more than three minutes to walk to a crossing, or if the distances between crossing points are over 200m, they may decide to cross along a more direct, but unsafe route.[15]

Grade-separated crossings, such as pedestrian underpasses, pedestrian overpasses, and footbridges, enable pedestrians to cross separately from vehicle traffic, but they allow motorists to drive at higher speeds, and many pedestrians will not use them if they can cross at street level (i.e., at-grade) in roughly the same amount of time.[16] For example, an observational study in India found that 85–95% of pedestrians continue to cross at-grade even when pedestrian bridges are available.[17]

Raised intersections, raised crossings, and raised mid-block crossings can reduce pedestrian crashes by 45%[18] by reducing vehicle travel speeds, improving visibility of pedestrians, and encouraging drivers to yield to pedestrians at the crossing.

Raised midblock crossings between intersections can allow pedestrians to cross in convenient locations where distances between marked crossings are too long for pedestrians.[19]

Grade-separated crossings are appropriate in cases where pedestrians must cross roadways, such as freeways and high-speed, high-volume arterials, or in areas where a large number of pedestrians will benefit.[20]

Signalized crossings, where drivers are required to give priority to pedestrians, are particularly needed where vehicle speeds are above 30 km/h.[21] All signalized crossings need ample time for pedestrians to cross at walking speed.

Providing footpaths can help prevent up to 60% of crashes involving pedestrians walking along a road.[22] Vehicle-pedestrian collisions are 1.5 to two times more likely to occur on roadways without footpaths.[23] For pedestrians to be able to use the footpaths, they must be of adequate width, in good condition, and free from obstructions that restrict their use (e.g., parked vehicles, signs, traders, utility poles). [24]

The implementation of pedestrian facilities demonstrates the adoption of the Safe System approach. The Safe System approach is a human-centric approach which dictates the design, use and operation of our road transport system to protect the human road users.[25]

A Safe System approach means any road safety intervention ought to ensure that the impact speed remains below the threshold likely to result in death or serious injury in the event of a crash. The human body, without physical protection, is not built to withstand impact forces greater than approximately 30 km/h.[26] Road infrastructure designs that cater to and protect pedestrians from vehicle speed demonstrate a human-centric approach.

History shows that countries that have adopted the Safe System approach implement evidence-based interventions, such as pedestrian zones, and tend to have the lowest rates of fatality per population and the fastest rates of reduction in fatality numbers.[27]

Pedestrian facilities save lives and reduce the severity of crash injuries, thereby reducing economic costs and positively contributing to a country’s economic growth. The economic costs related to injury and loss of life from traffic crashes include money needed to treat injuries, loss of hours worked, vehicle repair costs, insurance or third-party costs, and costs of traffic congestion caused by a crash.

A World Bank study highlighted that halving road crash deaths and injuries could generate additional flows of income, with increases in GDP per capita over 24 years as large as 7.1% in Tanzania, 7.2% in the Philippines, 14% in India, 15% in China, and 22.2% in Thailand.[28]

Infrastructure enhancements that improve walking conditions tend to increase property values and rents, attract new businesses, and increase local economic activity.[29]

We are all pedestrians at some point in our travels, regardless of the mode of transport used for the majority of our journey. We walk to work or to school, to take the bus or rail, or after parking the car.[30]

Walking provides affordable, basic transport and is a healthier and a more environmentally friendly mode of mobility than motorized transport.

Pedestrian facilities that improve walkability (safety, comfort, and accessibility) are a crucial step in creating sustainable and equitable transportation systems. [31]

The improvement of walking environments contributes to urban renewal, local economic growth, social cohesion, and air quality, and reduces the harmful effects of traffic noise.[32]

In Puebla, the Mobility Secretariat implemented low-cost infrastructure interventions in a school environment: widening pedestrian footpaths; installing bollards and horizontal signs, which reduced the length of a pedestrian crossing thereby reducing pedestrians’ exposure time crossing the road; and restructuring the parking area. A post-intervention evaluation showed a 69% decrease in road crashes overall, with the majority of this reduction being in crashes between pedestrians and vehicles.[33]

In Fortaleza, 50% of children traveling to a major public paediatric facility had to travel on a road that was congested with vehicles. Pedestrian footpaths were widened and raised crossings, speed humps, gateway treatments, lane and curve narrowing, and pedestrian ramps were installed. This resulted in a 42% reduction in the speed of vehicles, 67% reduction in crossing distance, and 86% reduction in pedestrians walking on the road. These interventions were part of the city efforts to improve road safety conditions, which also included enforcement, urban redesign, mass media campaigns, and improved data collection and analysis. All these efforts have resulted in a 35% reduction in road crash deaths since 2011.[34]

In Ho Chi Minh City, the local administration implemented over 300 road safety engineering measures across the city, including 157 refuge islands, 11 raised pedestrian crossings, eight footbridges, and 11 bus stops. These interventions are estimated to reduce fatalities and serious injuries by 42% from pre-intervention levels according to iRAP assessments.[35]

In Paris, France, the Boulevard de Magenta was one of the first projects of a program launched in the early 2000s for the widening of footpaths, construction of secure cycling lanes, tree planting, and a new dedicated bus lane protected by barriers. These interventions created a more attractive and pedestrian-oriented environment and a space that supports businesses. In the four years following the transformation, there were zero traffic fatalities. Additionally, the change decreased congestion and pollution.[36]

In 2015, Oslo committed to reducing road crashes and prioritizing the safety of pedestrians and cyclists. It implemented intersection improvements, for example, highly visible crosswalk markings on the road, increased the standard width of footpaths, and lowered speed limits. Between 2014 and 2018, they achieved a 41% decrease in the risk of fatal or serious injury for pedestrians, 47% decrease for cyclists, and 32% decrease for drivers on a trip-by-trip basis. No vulnerable road users were killed in 2019.[37]

Low-cost local safety schemes introduced on A404 Amersham Road showed a reduction in fatal and serious crashes from 12 to one between September 2007 and December 2010. The schemes involved improving pedestrian crossings along a segment where pedestrians were particularly at risk, reducing the speed limit in populated areas, improving the road markings, and high friction surface treatments that help reduce crashes, injuries, and fatalities associated with road friction in wet and snowy conditions. New streetlights and retro-reflective pavement markings were also installed to increase visibility at night.[38]

A major vehicle-dominated intersection in the Santana neighborhood in Sao Paulo, Brazil was redesigned with temporary interventions in September 2017. Pedestrian spaces around this intersection were expanded by shortening the crossings and creating curb extensions and a roundabout using materials that are low-cost, flexible and easy to install and reposition. They were a result of a collaboration between the local authorities and civil society where the city officials engaged civil society stakeholders to brainstorm and develop ideas. After an evaluation showing 82% of road users wanted the interventions to be made permanent, they were made permanent in June 2018. This led to a 32% reduction in travel speeds, and 89% of pedestrians and 72% of drivers reporting feeling safer at the intersection. These results led to similar redesigns in other neighborhoods and school zones in Sao Paulo. [39]

*Any travel speed reduction achieved via traffic calming measures has death and injury reduction benefits. In principle, a 1% reduction in average speed results in an approximate 2% decrease in injury crash frequency[40], a 3% decrease in severe crash frequency, and a 4% decrease in fatal crash frequency. Furthermore, 10 km/h reduction in a speed limit could be expected to produce around a 15–20% reduction in injury crashes, and up to around a 40% reduction in pedestrian fatal and serious injuries.[41]

The following guidance documents can support governments in the design and implementation of pedestrian facilities:

The extensive linkage between pedestrian facilities and the recommendations set out in existing key global road safety documents give more weight as to why this intervention ought to be implemented. Governments are able to demonstrate that they are putting recommended best practice into real practice when they implement the pedestrian facilities.

Implementing pedestrian facilities achieves, supports, and/or promotes the implementation of:

Page 11, box 1, point 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7: Multimodal transport and land-use planning

Page 12, box 2, points 1,2,3,4,5,6,7: Safe road infrastructure

Page 15, box 4, points 1, 3: Safe Road Use

Global Road Safety Performance Targets

Page 3:

Page 4:

Academic Expert Group of the 3rd Ministerial Conference on Global Road Safety

Recommendation 1: Page 7 and 28: “SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES AND REPORTING: including road safety interventions across sectors as part of SDG contributions.”

“In order to ensure the sustainability of businesses and enterprises of all sizes, and contribute to achievement of a range of Sustainable Development Goals including those concerning climate, health, and equity, we recommend that these organizations provide annual public sustainability reports including road safety disclosures, and that these organizations require the highest level of road safety according to Safe System principles in their internal practices, in policies concerning the health and safety of their employees, and in the processes and policies of the full range of suppliers, distributors and partners throughout their value chain or production and distribution system.“

Recommendation 2: Page 7 and 34: “PROCUREMENT: utilizing the buying power of public and private organizations across their value chains.

“In order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals addressing road safety, health,

climate, equity and education, we recommend that all tiers of government and the private sector prioritize road safety following a Safe System approach in all decisions, including the specification of safety in their procurement of fleet vehicles and transport services, in requirements for safety in road infrastructure investments, and in policies that incentivize safe operation of public transit and commercial vehicles.“

Recommendation 3: Page 7 and 37: “MODAL SHIFT: moving from personal motor vehicles toward safer and more active forms of mobility.

“In order to achieve sustainability in global safety, health and environment, we recommend that nations and cities use urban and transport planning along with mobility policies to shift travel toward cleaner, safer and affordable modes incorporating higher levels of physical activity such as walking, bicycling and use of public transit.“

Recommendation 4: Page 7 and 41: CHILD AND YOUTH HEALTH: encouraging active mobility by building safer roads and walkways.

“In order to protect the lives, security and well-being of children and youth and ensure the education and sustainability of future generations, we recommend that cities, road authorities and citizens examine the routes frequently traveled by children to attend school and for other purposes, identify needs, including changes that encourage active modes such as walking and cycling, and incorporate Safe System principles to eliminate risks along these routes.“

Recommendation 5: Page 7 and 44: INFRASTRUCTURE: realizing the value of Safe System design as quickly as possible.

“In order to realize the benefits that roads designed according to the Safe System approach will bring to a broad range of Sustainable Development Goals as quickly

and thoroughly as possible, we recommend that governments and all road authorities

allocate sufficient resources to upgrade existing road infrastructure to incorporate Safe System principles as soon as feasible.”

Recommendation 7: Page 7 and 52: ZERO SPEEDING: protecting road users from crash forces beyond the limits of human injury tolerance.

“In order to achieve widespread benefits to safety, health, equity, climate and quality of life, we recommend that businesses, governments and other fleet owners practice a zero-tolerance approach to speeding and that they collaborate with supporters of a range of Sustainable Development Goals on policies and practices to reduce speeds to levels that are consistent with Safe System principles using the full range of vehicle, infrastructure, and enforcement interventions.“

Recommendation 8: Page 7 and 56: 30 KM/H: mandating a 30 km/h speed limit in urban areas to prevent serious injuries and deaths to vulnerable road users when human errors occur.

“In order to protect vulnerable road users and achieve sustainability goals addressing

livable cities, health and security, we recommend that a maximum road travel speed limit of 30 km/h be mandated in urban areas unless strong evidence exists that higher speeds are safe.“

Recommendation 9: Page 7 and 59: TECHNOLOGY: bringing the benefits of safer vehicles and infrastructure to lowand middle-income countries.

“In order to quickly and equitably realize the potential benefits of emerging technologies to road safety, including, but not limited to, sensory devices, connectivity methods and artificial intelligence, we recommend that corporations and governments incentivize the development, application and deployment of existing and future technologies to improve all aspects of road safety from crash prevention to emergency response and trauma care, with special attention given to the safety needs and social, economic and environmental conditions of low- and middle-income nations.“

Page 14: Leadership on road safety

“Create an agency to spearhead road safety

Develop and fund a road safety strategy

Evaluate the impact of road safety strategies

Monitor road safety by strengthening data systems

Raise awareness and public support through education and campaigns”

Page 14: Infrastructure design and improvement

“Provide safe infrastructure for all road users including sidewalks, safe crossings, refuges, overpasses and underpasses

Put in place bicycle and motorcycle lanes

Make the sides of roads safer by using clear zones, collapsible structures or barriers

Design safer intersections

Separate access roads from through-roads

Prioritize people by putting in place vehicle-free zones

Restrict traffic and speed in residential, commercial and school zones

Provide better, safer routes for public transport”

Page 14: Vehicle Safety

“Establish and enforce motor vehicle safety standard regulations related to:

seat-belts;

seat-belt anchorages;

frontal impact;

side impact;

electronic stability control;

pedestrian protection; and

ISOFIX child restraint points

Establish and enforce regulations on motorcycle anti-lock braking and daytime

running lights”

A/RES/76/294 Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Improving Global Road Safety

Page 3-5:

“1. Drive the implementation of the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030, which describes key suggested actions to achieve the reduction in road traffic deaths of at least 50 per cent by 2030 and calls for setting national targets to reduce fatalities and serious injuries for all road users with special attention given to the safety needs of those road users who are the most vulnerable to road-related crashes, including pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists and users of public transport, taking into account national circumstances, policies and strategies;

2. Develop and implement regional, national and subnational plans that may include road safety targets or other evidence-based indicators where they have been set, and put in place evidence-based implementation processes by adopting a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach and designating national focal points for road safety with the establishment of their networks in order to facilitate cooperation with the World Health Organization to track progress towards the implementation of the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030;

4. Implement a Safe System approach through policies that foster safe urban and rural road infrastructure design and engineering; set safe adequate speed limits supported by appropriate speed management measures; enable multimodal transport and active mobility; establish, where possible, an optimal mix of motorized and non-motorized transport, with particular emphasis on public transport, walking and cycling, including bike-sharing services, safe pedestrian infrastructure and level crossings, especially in urban areas;

5. Adopt evidence- and/or science-based good practices for addressing key risk factors, including the non-use of seat belts, child restraints and helmets, medical conditions and medicines that affect safe driving, driving under the influence of alcohol, narcotic drugs and psychotropic and psychoactive substances, inappropriate use of mobile phones and other electronic devices, including texting while driving, speeding, driving in low visibility conditions, driver fatigue, as well as the lack of appropriate infrastructure; and for enforcement efforts, including road policing, coupled with awareness and education initiatives, supported by infrastructure designs that are intuitive and favour compliance with legislation and a robust emergency response and post-crash care system;

6. Ensure that road infrastructure improvements and investments are guided by an integrated road safety approach that, inter alia, takes into account the connections between road safety and eradication of poverty in all its dimensions, physical health, including visual impairment and mental health issues, the achievement of universal health coverage, economic growth, quality education, reducing inequalities within and among countries, gender equality and women’s empowerment, decent work, sustainable cities, environment and climate change, as well as the broader social determinants of road safety and the interdependence between Sustainable Development Goals and targets that are integrated, interlinked and indivisible, and assures minimum safety performance standards for all road users;

9. Integrate a gender perspective into all policymaking and implementation of transport policies that provide for safe, secure, inclusive, accessible, reliable and sustainable mobility, and non-discriminatory participation in transport; and ensure that policies cater to road users who might be in vulnerable situations, in particular children, youth, older persons and persons with disabilities;

10. Deliver evidence-based road safety knowledge and awareness programmes to promote a culture of safety among all road users and to address high-risk behaviours, especially among youth, and the broader road-using community through advocacy, training and education and encourage private sector participation in supplementing national efforts in promoting greater road safety awareness as part of corporate social responsibility;

12. Acknowledge the importance of adequate, predictable, sustainable and timely international financing without conditionalities in complementing the efforts of countries in mobilizing resources domestically, especially in low- and middle-income countries; support the demands of financing in developing countries by leveraging the United Nations Road Safety Fund and other dedicated mechanisms, as appropriate, for promoting safe road transport infrastructure and for supporting the implementation of measures required to meet the voluntary global performance targets, including by supporting the voluntary replenishment of all United Nations system road safety funds and mechanisms;

13. Promote capacity-building, knowledge-sharing, technical support and technology transfer programmes and initiatives on mutually agreed terms in the area of road safety, especially in developing countries, which confront unique challenges and, where possible, the integration of such programmes and initiatives into sustainable development assistance programmes through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation formats, as well as public-private collaboration;

14. Promote the development, knowledge-sharing and deployment of vehicle automation and new technologies in traffic management using both intelligent transport systems and cooperative intelligent transport systems, in line with national requirements, to improve accessibility and all aspects of road safety while also monitoring, assessing, managing and mitigating challenges associated with rapid technological change and increasing connectivity;

15. Contribute to international and national road safety by encouraging research and improving and harmonizing disaggregated data collection on road safety, including data on road traffic crashes, resulting deaths and injuries, and road infrastructure, including those gathered from regional road safety observatories, to better inform policies and actions; strengthen road safety data capacity, including in low- and middle-income countries, and improve the quality of systematic and consolidated data collection and comparability at the international level for effective and evidence-based policymaking and implementation while taking into account privacy and national security considerations; and request the World Health Organization to continue to monitor and report on progress towards the achievement of the goals of the decade of action;

16. Leverage the full potential of the multilateral system, in particular the World Health Organization, the good offices of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Road Safety, the United Nations regional commissions and relevant United Nations entities, as well as other stakeholders, including the Global Road Safety Partnership, to support Member States with dedicated technical assistance and, upon their request, in applying voluntary global performance targets for road safety when appropriate;

17. Request the Secretary-General to provide, in consultation with the World Health Organization and other relevant agencies, a progress report during the seventy-eighth and eightieth sessions of the General Assembly, including recommendations on the implementation of the present declaration towards improving global road safety, which will serve to inform the high-level meeting to be convened in 2026;

[1] Our definition is based on the following sources:

Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Global Street Design Guide. Island Press, February, 426.

[2] Vergel-Tovar, E., López, S., Lleras, N., Hidalgo, D., Rincón, M., Orjuela, S., & Vega, J. (2020). Examining the relationship between road safety outcomes and the built environment in Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Road Safety, 31(3), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.33492/jrs-d-20-00254.

[3] Zegeer, C.V., Seiderman, C., Lagerwey, P., Cynecki, M., Ronkin, M., & Schneide, R. (2002). Pedestrian facilities users guide. Providing safety and mobility. FHWA-RD-01-102, March, 164.

Washington State Department of Transportation. (1997). Pedestrian Facilities Guidebook Incorporating Pedestrians into Washington’s Transportations System. Otak, Olympia, Washington, September, 248.

[4] Washington State Department of Transportation. (1997). Pedestrian Facilities Guidebook Incorporating Pedestrians into Washington’s Transportations System. Otak, Olympia, Washington, September, 248.

[5] Zegeer, C.V., Seiderman, C., Lagerwey, P., Cynecki, M., Ronkin, M., & Schneide, R. (2002). Pedestrian facilities users guide. Providing safety and mobility. FHWA-RD-01-102, March, 164.

[6] Washington State Department of Transportation. (1997). Pedestrian Facilities Guidebook Incorporating Pedestrians into Washington’s Transportations System. Otak, Olympia, Washington, September, 248.

[7]World Health Organization. (2021). Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030.

[8] World Health Organization. (2018). Global status report on road safety 2018. Geneva.

[9] Sharpin, A.B, Adriazola-Steil, C., Job, S., et al. (2021). Low-Speed Zone Guide. World Resources Institute and The Global Road Safety Facility.

[10] Global Road Safety Facility. (2023). Speed Management Hub – Frequently Asked Questions, Note 8.2.

[11] Sharpin, A.B, Adriazola-Steil, C., Job, S., et al. (2021). Low-Speed Zone Guide. World Resources Institute and The Global Road Safety Facility.

[12] World Health Organization. (2013). Pedestrian safety: A road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[13] World Health Organization. (2013). Pedestrian safety: A road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[14] World Health Organization. (2013). Pedestrian safety: A road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[15] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Pedestrian Crossing – Global Street Design Guide. Island Press; 2nd None ed. edition.

[16] Zegeer, C.V., Seiderman, C., Lagerwey, P., Cynecki, M., Ronkin, M., & Schneide, R. (2002). Pedestrian facilities users guide. Providing safety and mobility. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, FHWA-RD-01-102.

[17] Institute for Transportation & Development Policy. (2019). Pedestrian Bridges Make Cities Less Walkable. Why do Cities Keep Building Them?

[18] Zegeer, C.V., Nabors, D., Lagerwey, P. (2013). Raised Pedestrian Crossings – Pedestrian Safety Guide and Countermeasure Selection System. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

[19] Aparadian, R. & Alam, B.M. (2017). A Study of Effectiveness of Midblock Pedestrian Crossings; Analyzing a Selection of High-Visibility Warning Signs. Interdisciplinary Journal of Signage and Wayfinding;1 (2).

[20] Otak. (1997). Pedestrian Facilities Guidebook – Incorporating Pedestrians Into Washington’s Transportation System. Washington State Department of Transportation.

[21] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Pedestrian Crossing – Global Street Design Guide. Island Press; 2nd None ed. edition

[22] Turner, B., Job, S. & Mitra, S. (2021). Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work. Washington, DC., USA: World Bank.

[23] Knoblauch, R.L., Tustin, B.H., Smith, S.A., & Pietrucha, M.T. (1988). Investigation of Exposure Based Pedestrian Accident Areas: Crosswalks, Sidewalks, Local Streets and Major Arterials. Federal Highway Administration, McLean, VA. Office of Research, Development, and Technology.

[24] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Pedestrian Crossing – Global Street Design Guide. Island Press; 2nd None ed. edition.

[25] World Road Association. (2019). The Safe System Approach – Road Safety Manual: A Manual for Practitioners and Decision Makers on Implementing Safe System Infrastructure.

[26] International Transport Forum. (2008), Towards Zero: Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[27] https://www.wri.org/research/sustainable-and-safe-vision-and-guidance-zero-road-deaths.

[28] World Bank. (2017). The High Toll of Traffic Injuries: Unacceptable and Preventable. World Bank.

[29] Tolley, R. (2011), Good For Busine$$ – The Benefits Of Making Streets More Walking And Cycling Friendly, Discussion paper, Heart Foundation South Australia.

[30] Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs India and ITDP. (2019). Complete Streets Implementation Workbook

[36] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Global Street Design Guide. Island Press, February.

[41] Turner, B., Job, S., & Mitra, S. (2021). Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work. World Bank, Washington, DC., USA.

Elvik, R.(2009). The power model of the relationship between speed and road safety. Update and new analyses. Institute of Transportation Economics. TOI Report 1034/2009.

Mitra, S., Job, S., Han, S., & Eom, K. (2021). Do Speed Limit Reductions Help Road Safety? Do Speed Limit Reductions Help Road Safety?, June.

OECD/International Transport Forum. (2018). Speed and crash risk. ITF (International Transport Forum).

[44] International Road Assessment Programme, iRAP. (2022). The Road Safety Toolkit.

[46] Corporation of Chennai. (2014). Non motorized transport policy. Corporation of Chennai

[48] Street Plans. Tactical Urbanist’s Guide to getting it done