A law mandating the correct use of helmets by motorcycle drivers and passengers of all ages while riding motorcycles. The law must also require the helmets to meet the safety standard (national or international), i.e., demonstrated to be effective in reducing head injuries for motorcycle riders. The law must be combined with enforcement that applies penalties for non-compliance and promotion that warns people about the law, enforcement, and penalties.

Countries that allow motorcycles on public roads.

The Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030 (Global Plan)[2] sets a target to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030. Achieving this target requires implementation of evidence-based interventions that are known to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries. Motorcycle helmet law, combined with enforcement and publicity are one such evidence-based intervention.

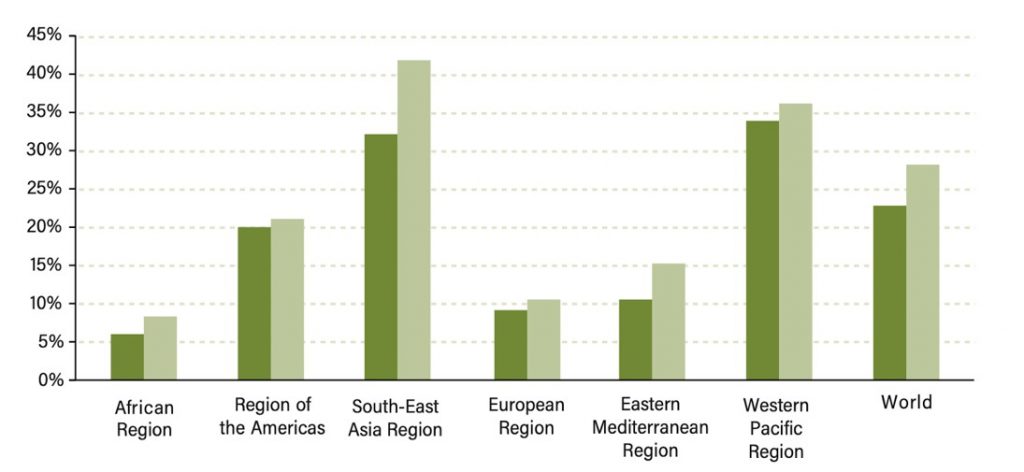

Two- and three-wheelers account for 28% of all road traffic fatalities worldwide. South-East Asia and the Western Pacific regions report the highest numbers of two- and three-wheeler fatalities: 43% and 36% respectively. All regions are seeing an increase in motorcyclist fatality rates (Figure 1).[3]

Motorcycles are widely used in many countries for personal and public transport as well as for service delivery. Most low- and middle-income countries have seen a significant increase in the use of motorcycles due to the high cost of other modes of transportation and in response to an increase in traffic congestion in urban areas.[5] However, motorcycle riding remains one of the most unsafe forms of transport.[6]

Unlike car occupants who may have crash protection from airbags and seat belts, motorcycle users lack crash protection, making them particularly vulnerable to traffic related fatalities and injuries.[7] Motorcycle riders are 27 times more likely to die in a traffic crash than car occupants and are about six times as likely to be injured.[8]

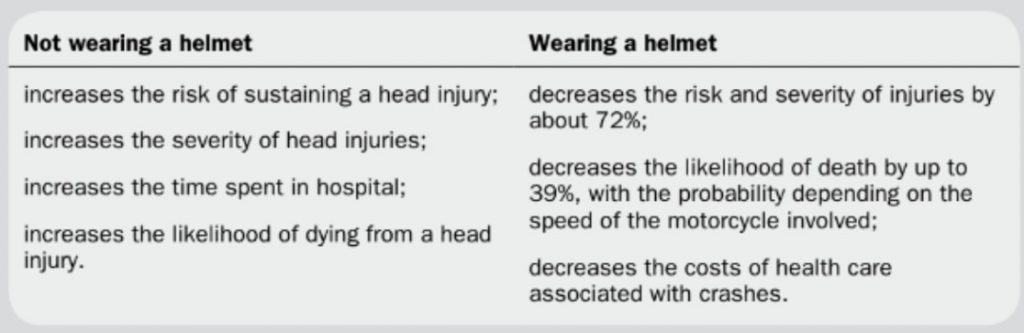

Injuries to the head and neck are among the main causes of death and severe injury to two- and three-wheeled vehicle users.[9] A motorcycle helmet reduces the impact of acceleration-deceleration forces to the brain, as well the impact of the direct contact with an object or surface at the moment of a crash.[10]

Using helmets can decrease the risk of death in a motorcycle crash by 39% and serious injuries by 72%.[11] (Figure 2)

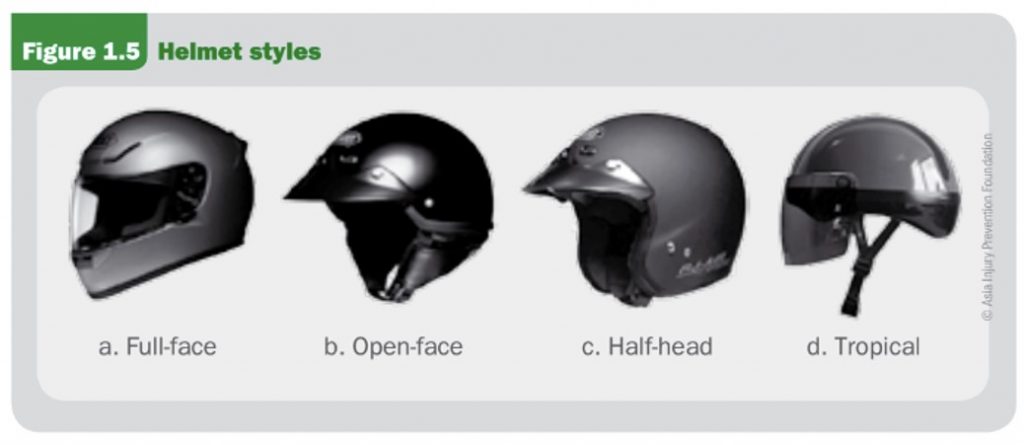

The full benefit of death and serious injury reduction from motorcycle helmet use depends on the amount of face coverage (see different styles in Figure 3) and whether the helmet is appropriately fastened and meets helmet standards. Full-face helmets provide the highest level of protection against crash related head and neck injuries than other types of helmet.[13] Helmets must be fully fastened[14] and follow helmet standards[15] (e.g., UN Regulation No.22, ECE-22[16]) to be effective. A helmet law, enforcement, and publicity must therefore cover all these aspects.

In places where the helmet law, enforcement and promotion are executed together, helmet wearing rate reaches over 95%.[18] Increased helmet wearing achieved through the three elements of law, enforcement, and promotion decrease fatal and nonfatal injuries. In particular, motorcycle-related head injuries are reduced by as much as 33% and the severity of the injury is reduced.[19],[20]

A universal helmet law—that applies to all motorcycle drivers and passengers irrespective of age and gender on all public roads in both rural and urban settings—is much more effective in increasing helmet wearing and reducing fatal and nonfatal motorcycle crash injuries than a law that exempts certain groups or settings.[21]

A helmet law with exemptions is more difficult to enforce, making it less effective than a universal helmet law. For example, if a law exempts helmet wearing based on the age of the rider, it is very difficult for enforcement officers to single out how old a rider is when s/he is riding past on a motorcycle.[22]

The helmet law and standards must also consider the size of children. Children’s helmet wearing rates are often found to be lower than adults’ in some countries.[23] Children not wearing a helmet are more likely to be injured and their injuries more severe than those wearing a helmet in the event of a motorcycle crash.[24] However, currently, the smallest helmet size regulated by standards would approximately fit the head of a five- to seven-year-old child.[25]

A helmet law, no matter how comprehensive, could not have the full effect of correct helmet use without enforcement that effectively applies penalties for noncompliance.[26]

Promotion—that informs motorcycle riders about enforcement of the helmet-wearing law, the penalties for noncompliance, and why helmet wearing is being enforced (i.e., to protect motorcycle riders from head and brain injuries)—generates greater compliance with the law.[27]

Promotion also warns people what is illegal and that they may receive an unattractive penalty for noncompliance. This should be done in advance of enforcement to give motorcycle riders time to purchase the right helmet. This creates a perception of fairness, making the law and enforcement more effective.[28] However, promotion without the law or enforcement will not increase helmet use or reduce deaths and injuries to the same degree.

The Safe System approach is a human-centric approach which dictates the design, use and operation of our road transport system to protect the human road users.[29] The human body, without physical protection, is not built to withstand impact forces greater than approximately 30 km/h and the inherent lack of crash protection to motorcycle riders puts them at a higher risk for injuries and deaths and injuries of greater severity.[30] Correct wearing of standard motorcycle helmets protects the heads of riders.

Motorcycle helmet law, enforcement and promotion together save lives and reduce the severity of crash injuries, thereby reducing economic costs and positively contributing to a country’s economic growth.

The economic costs related to injury and loss of life from traffic crashes include money needed to treat injuries, loss of hours worked, vehicle repair costs, insurance or third-party costs, and costs of congestion from a crash.

A World Bank study highlighted that halving road crash deaths and injuries could generate additional flows of income, with increases in GDP per capita over 24 years as large as 7.1% in Tanzania, 7.2% in the Philippines, 14% in India, 15% in China, and 22.2% in Thailand.[31]

In Thailand, a helmet law was enacted nationwide in 1994, legally mandating the wearing of a helmet by motorcycle drivers and passengers. Immediately after enactment, the helmet law was enforced for 90 days in Bangkok, 180 days in 17 provinces, and 360 days in the rest of the country. In Khon Kaen province, the helmet law was widely promoted, and these campaigns continued even after the police began issuing fines. With the combination of helmet law, enforcement, and promotion, helmet wearing in Khon Kaen increased five-fold, head injuries decreased by 41.4%, and deaths decreased by 20.8%.[32]

In Italy, only motorcycle drivers (not passengers) were legally required to wear helmets and moped drivers over the age of 18 were exempt. In 2000, a much more comprehensive law, requiring the use of helmets by all motorcycle and moped drivers and passengers, irrespective of age, was adopted and combined with enforcement and promotion. Across the country, helmet-wearing rates rose up to 95% in some areas, hospital admissions for traumatic brain injury declined by 66%, and the number of blunt head injuries (epidural haemorrhages) involving motorcycle and moped riders was almost eliminated.[33]

In 2007, the Vietnamese government enacted, promoted, and implemented a new helmet law mandating all motorcycle drivers and passengers to wear helmets on all roads. National data showed that the combination of helmet law, enforcement, and promotion reduced road traffic deaths by 18% in the first three months and saved around 1,557 lives and prevented 2,495 serious injuries in the first year.[34] According to another analysis, the law prevented 20,609 deaths and 412,175 serious injuries from 2008 to 2013, and by 2013, over 90% of Vietnamese motorcyclists were wearing helmets.[35]

An observational helmet use study between June 2011 and December 2014 found that correct helmet use increased from 34.3% to 76.9% in Ha Nam and from 68.9% to 72.2% in Ninh Binh. This result was attributed to enforcement and promotion of the law and benefits of correctly wearing standard helmets.[36]

*In principle, wearing a motorcycle helmet reduces the risk and severity of injuries by around 70% and the likelihood of death by up to 40%.[37] Therefore, any increase in the correct helmet use achieved via a comprehensive law with enforcement and associated promotion has death and injury reduction benefits.[38]

The following guidance documents can support governments in the design and implementation of motorcycle helmet law, enforcement, and promotion:

Implementing motorcycle helmet law, enforcement, and promotion achieves, supports, and/or promotes the implementation of:

Page 13, box 3, points 1: Vehicle Safety

Page 15, box 4, points 1, 3, 4: Safe Road Use

Global Road Safety Performance Targets

Page 3:

Page 4:

Academic Expert Group of the 3rd Ministerial Conference on Global Road Safety

Recommendation 1: Page 7 and 28: “SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES AND REPORTING: including road safety interventions across sectors as part of SDG contributions.”

“In order to ensure the sustainability of businesses and enterprises of all sizes, and contribute to achievement of a range of Sustainable Development Goals including those concerning climate, health, and equity, we recommend that these organizations provide annual public sustainability reports including road safety disclosures, and that these organizations require the highest level of road safety according to Safe System principles in their internal practices, in policies concerning the health and safety of their employees, and in the processes and policies of the full range of suppliers, distributors and partners throughout their value chain or production and distribution system.“

Recommendation 2: Page 7 and 34: “PROCUREMENT: utilizing the buying power of public and private organizations across their value chains.

“In order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals addressing road safety, health,

climate, equity and education, we recommend that all tiers of government and the private sector prioritize road safety following a Safe System approach in all decisions, including the specification of safety in their procurement of fleet vehicles and transport services, in requirements for safety in road infrastructure investments, and in policies that incentivize safe operation of public transit and commercial vehicles.“

Recommendation 4: Page 7 and 41: CHILD AND YOUTH HEALTH: encouraging active mobility by building safer roads and walkways.

“In order to protect the lives, security and well-being of children and youth and ensure the education and sustainability of future generations, we recommend that cities, road authorities and citizens examine the routes frequently traveled by children to attend school and for other purposes, identify needs, including changes that encourage active modes such as walking and cycling, and incorporate Safe System principles to eliminate risks along these routes.“

Recommendation 9: Page 7 and 59: TECHNOLOGY: bringing the benefits of safer vehicles and infrastructure to lowand middle-income countries.

“In order to quickly and equitably realize the potential benefits of emerging technologies to road safety, including, but not limited to, sensory devices, connectivity methods and artificial intelligence, we recommend that corporations and governments incentivize the development, application and deployment of existing and future technologies to improve all aspects of road safety from crash prevention to emergency response and trauma care, with special attention given to the safety needs and social, economic and environmental conditions of low- and middle-income nations.“

Page 14: Leadership on road safety

“Create an agency to spearhead road safety

Develop and fund a road safety strategy

Evaluate the impact of road safety strategies

Monitor road safety by strengthening data systems

Raise awareness and public support through education and campaigns”

Page 14: Enforcement of traffic laws

“Establish and enforce laws at national, local and city levels on:

drinking and driving;

motorcycle helmets;

seat-belts; and

child restraints“

A/RES/76/294 Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Improving Global Road Safety

Page 3-5:

“1. Drive the implementation of the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030, which describes key suggested actions to achieve the reduction in road traffic deaths of at least 50 per cent by 2030 and calls for setting national targets to reduce fatalities and serious injuries for all road users with special attention given to the safety needs of those road users who are the most vulnerable to road-related crashes, including pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists and users of public transport, taking into account national circumstances, policies and strategies;

2. Develop and implement regional, national and subnational plans that may include road safety targets or other evidence-based indicators where they have been set, and put in place evidence-based implementation processes by adopting a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach and designating national focal points for road safety with the establishment of their networks in order to facilitate cooperation with the World Health Organization to track progress towards the implementation of the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030;

3. Promote systematic engagement with relevant stakeholders, including from transport, health, education, finance, environmental and infrastructure areas, and encourage Member States to consider becoming contracting parties to the United Nations legal instruments on road safety and, beyond accession, applying, implementing and promoting their provisions or safety regulations;

5. Adopt evidence- and/or science-based good practices for addressing key risk factors, including the non-use of seat belts, child restraints and helmets, medical conditions and medicines that affect safe driving, driving under the influence of alcohol, narcotic drugs and psychotropic and psychoactive substances, inappropriate use of mobile phones and other electronic devices, including texting while driving, speeding, driving in low visibility conditions, driver fatigue, as well as the lack of appropriate infrastructure; and for enforcement efforts, including road policing, coupled with awareness and education initiatives, supported by infrastructure designs that are intuitive and favour compliance with legislation and a robust emergency response and post-crash care system;

6. Ensure that road infrastructure improvements and investments are guided by an integrated road safety approach that, inter alia, takes into account the connections between road safety and eradication of poverty in all its dimensions, physical health, including visual impairment and mental health issues, the achievement of universal health coverage, economic growth, quality education, reducing inequalities within and among countries, gender equality and women’s empowerment, decent work, sustainable cities, environment and climate change, as well as the broader social determinants of road safety and the interdependence between Sustainable Development Goals and targets that are integrated, interlinked and indivisible, and assures minimum safety performance standards for all road users;

10. Deliver evidence-based road safety knowledge and awareness programmes to promote a culture of safety among all road users and to address high-risk behaviours, especially among youth, and the broader road-using community through advocacy, training and education and encourage private sector participation in supplementing national efforts in promoting greater road safety awareness as part of corporate social responsibility;

12. Acknowledge the importance of adequate, predictable, sustainable and timely international financing without conditionalities in complementing the efforts of countries in mobilizing resources domestically, especially in low- and middle-income countries; support the demands of financing in developing countries by leveraging the United Nations Road Safety Fund and other dedicated mechanisms, as appropriate, for promoting safe road transport infrastructure and for supporting the implementation of measures required to meet the voluntary global performance targets, including by supporting the voluntary replenishment of all United Nations system road safety funds and mechanisms;

13. Promote capacity-building, knowledge-sharing, technical support and technology transfer programmes and initiatives on mutually agreed terms in the area of road safety, especially in developing countries, which confront unique challenges and, where possible, the integration of such programmes and initiatives into sustainable development assistance programmes through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation formats, as well as public-private collaboration;

14. Promote the development, knowledge-sharing and deployment of vehicle automation and new technologies in traffic management using both intelligent transport systems and cooperative intelligent transport systems, in line with national requirements, to improve accessibility and all aspects of road safety while also monitoring, assessing, managing and mitigating challenges associated with rapid technological change and increasing connectivity;

15. Contribute to international and national road safety by encouraging research and improving and harmonizing disaggregated data collection on road safety, including data on road traffic crashes, resulting deaths and injuries, and road infrastructure, including those gathered from regional road safety observatories, to better inform policies and actions; strengthen road safety data capacity, including in low- and middle-income countries, and improve the quality of systematic and consolidated data collection and comparability at the international level for effective and evidence-based policymaking and implementation while taking into account privacy and national security considerations; and request the World Health Organization to continue to monitor and report on progress towards the achievement of the goals of the decade of action;

16. Leverage the full potential of the multilateral system, in particular the World Health Organization, the good offices of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Road Safety, the United Nations regional commissions and relevant United Nations entities, as well as other stakeholders, including the Global Road Safety Partnership, to support Member States with dedicated technical assistance and, upon their request, in applying voluntary global performance targets for road safety when appropriate;

[1] Our definition is based on the following sources:

[2]World Health Organization. (2021). Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030

[3] World Health Organization. (2018). Global status report on road safety 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization

[4] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[5] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[6] UNESCAP. (2019). Strategies to Tackle the Issue of Speed for Road Safety in the Asia-Pacific Region: Implementation Framework. UNESCAP, Bangkok.

[7] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[8] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva

[9] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[10] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[11] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva

[12] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva

[13] Chaichan, S., Asawalertsaeng, T., Veerapongtongchai, P., Chattakul, P., Khamsai, S., Pongkulkiat, P., & Sawanyawisuth, K. (2020). Are full-face helmets the most effective in preventing head and neck injury in motorcycle accidents? A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports, 13;19:101118.

[14] Thai, K.T., McIntosh, A.S., & Pang, T.Y. (2015). Factors affecting motorcycle helmet use: size selection, stability, and position. Traffic injury prevention, 16(3), 276-282.

[15] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva.

[16] United Nations. (2002). Addendum 21: Regulation No. 22. Revision 4.

[17] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[18] Passmore, J.W., Nguyen, L.H., Nguyen, N.P., & Olivé, J-M. (2010). The formulation and implementation of a national helmet law: a case study from Viet Nam. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88 (10), 783 – 787.

[19] Lee, J. Mandatory helmet legislation as a policy tool for reducing motorcycle fatalities: pinpointing the efficacy of universal helmet laws. Accident Analysis & Prevention,111, 173-183.

[20] McGwin, G.J. Jr, Whatley, J., Metzger, J., Valent, .F, Barbone, F., & Rue, L.W. (2004). The effect of state motorcycle licensing laws on motorcycle driver mortality rates. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 56(2):p 415-419.

[21] Peng, Y., Vaidya, N., Finnie, R., Reynolds, J., Dumitru, C., Njie, G., Elder, R., Ivers, R., Sakashita, C., Shults, R.A., Sleet, D.A., & Compton, R.P. (2017). Community Preventive Services Task Force. Universal Motorcycle Helmet Laws to Reduce Injuries: A Community Guide Systematic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine;52(6):820-832.

[22] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[23] Lambrosquini, F., González, F., Bottinelli, E., et al. (2017). Study on the Conditions for Children Transport on Motorcycles in Latin America. Fundación Gonzalo Rodríguez.

[24] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva.

[25] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva

[26] World Health Organization. (2017). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva

World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva

[27] Bao, J., Bachani, A.M., Cuong, P., Ngoc Quang, L., Nguyen, N., & Hyder, A. (2017). Trends in motorcycle helmet use in Vietnam: results from a four-year study. Public Health; 144:S39-S44.

[28] Sakashita, C., Fleiter, J.J., Cliff, D., Flieger, M., Harman, B., & Lilley, M. (2021). A Guide to the Use of Penalties to Improve Road Safety. Global Road Safety Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland.

[29] World Road Association. (2019). The Safe System Approach – Road Safety Manual: A Manual for Practitioners and Decision Makers on Implementing Safe System Infrastructure.

[30] Chawla, H., Karaca, I., & Savolainen, P.T. (2019). Contrasting Crash- and Non-Crash-Involved Riders: Analysis of Data from the Motorcycle Crash Causation Study. Transportation Research Record, 2673(7), 122–131.

[31] World Bank. (2017). The High Toll of Traffic Injuries: Unacceptable and Preventable. World Bank.

[32] Ichikawa, M., Chadbunchachai, W., & Marui, E. Effect of the helmet act for motorcyclists in Thailand. Accident; Analysis and Prevention. 2003 Mar;35 (2):183-189. DOI: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00102-6. PMID: 12504139.

[33] P. 19, World Health Organization, (2006), Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. Geneva.

[34] P. 181-186, Glassman, A., & Temin, M. (2016). Millions Saved New Cases Of Proven Success In Global Health. Brookings Institution Press And Center for Global Development.; Passmore, J.W., Nguyen, L.H., Nguyen, N.P., & Olivé, J-M. (2010). The formulation and implementation of a national helmet law: a case study from Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 88 (10), 783-7.

[35] Asia Injury Prevention Foundation. 2014. Developing an Integrated Campaign to Address Child Helmet Use in Vietnam: A Case Study. New York: Atlantic Philanthropies.

[36] Bao, J., Bachani, A.M., Viet, C.P., Quang, L.N., Nguyen, N., & Hyder, A.A. (2017). Trends in motorcycle helmet use in Vietnam: results from a four-year study. Public Health, 144, S39–S44.

[37] World Health Organization, (2006), Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. Geneva.

[38] World Health Organization, (2006), Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. Geneva.

Peng, Y., Vaidya, N., Finnie, R., Reynolds, J., Dumitru, C., Njie, G., Elder, R., Ivers, R., Sakashita, C., Shults, R.A., Sleet, D.A., & Compton, R.P. (2017). Universal Motorcycle Helmet Laws to Reduce Injuries: A Community Guide Systematic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(6), 820–832.

Olsen, C.S., Thomas, A.M., Singleton, M., Gaichas, A.M., Smith, T.J., Smith, G.A., Peng, J., Bauer, M.J., Qu, M., Yeager, D., Kerns, T., Burch, C., & Cook, L.J. (2016). Motorcycle helmet effectiveness in reducing head, face and brain injuries by state and helmet law. Injury Epidemiology, 3(1).

[39] World Health Organization. (2022). Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, 2nd Edition. WHO, Geneva.

[40] World Health Organization. (2006). Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. WHO, Geneva.

[41] United Nations. (2002). Addendum 21: Regulation No. 22. Revision 4.

[42] Sakashita, C. Fleiter, J.J, Cliff, D., Flieger, M., Harman, B. & Lilley, M (2021). A Guide to the Use of Penalties to Improve Road Safety. Global Road Safety Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland.