Traffic calming measures reduce speed of traffic in areas where pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists are present, road infrastructure safety quality is poor, and/or vehicles enter a built-up area on a rural road. Traffic calming measures include:

Areas where pedestrians need to cross the road, where vehicles enter and drive through a built-up area or where pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists are present. In practice, this would include residential areas, villages, markets, retirement villages, school zones, healthcare and hospital precincts, around places of worship, university hubs, public transport hubs and major train station zones, city centers, and central business districts (CBD).

and/or

Areas where deaths or serious injuries occur among any road users from road crashes, regardless of the road function.

The Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030 (Global Plan)[2] sets a target to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030. Achieving this target requires implementation of evidence-based interventions that are known to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries. Traffic calming measures are one such evidence-based intervention.

Traffic calming measures are designed to ensure that approaching vehicles reduce their travel speed (self-explaining design).[3]

Speed humps and raised crossings, for example, can reduce the 85th percentile travel speed (a speed at or below which 85% of traffic will be traveling): an 18%[4] reduction was reported in the United States of America and a 30%[5] reduction in Tanzania.

Gateway treatments, which alert drivers that they are entering a low-speed area, are shown to be effective in reducing travel speeds by 11–17 km/h as well as reducing fatal and serious crashes by 23%.[6]

Traffic calming measures, because they reduce speed, can lead to up to 40% reduction in road crashes and in the severity of crashes.[7]

In Ghana, the mean vehicle speeds, the proportion of vehicles exceeding the 50 km/h speed limit (30% vs 60%), and the odds of pedestrian fatality were significantly lower in settlements with traffic calming measures than those without.[8]

In Bogota, Colombia, driver compliance with the speed limit increased from an average of 29% to 86% when 30 km/h speed limit signs were complemented with traffic calming measures.[9]

The self-explaining design of traffic calming measures may be more workable than increased police enforcement in low- and middle-income settings. Rumble strips on the main Accra-Kumasi highway in Ghana, for example, reduced crashes by about 35% and fatalities by about 55%.[10]

Drivers traveling at higher speeds have reduced levels of peripheral awareness due to a narrower field of vision. This impedes their ability to quickly predict or detect potential conflicts on the road.[11] Traffic calming measures, such as raised intersections and raised midblock crossings, reduce vehicle travel speeds, improve visibility of pedestrians, and encourage drivers to yield to pedestrians at the crossing.[12]

Intersections are particularly dangerous conflict points between different road users. Designing intersections as a single-lane roundabout can reduce the number of collisions and injuries.[13] Well-designed roundabouts may contribute to reductions in fatalities and serious injury by between 70% and 80%.[14] The tight circle of a roundabout forces drivers to slow down and the circular travel pattern reduces the likelihood of some of the most severe forms of intersection crashes (e.g., head on, right angle and left turn collisions).

The Safe System approach is a human-centric approach which dictates the design, use and operation of our road transport system to protect the human road users.[15]

A Safe System approach means any road safety intervention ought to ensure that the impact speed remains below the threshold likely to result in death or serious injury in the event of a crash. Depending on the level of protection that the road users have and the type of crash, this threshold will vary. Typically, the impact speed must remain below 30 km/h for a pedestrian hit by a vehicle, below 50 km/h for a properly restrained motor vehicle occupant in a side impact crash, and below 70 km/h for a properly restrained motor vehicle occupant in a head-on crash.[16] Road infrastructure designs that self-explain and self-enforce approaching vehicles to slow down and effectively reduce vehicles’ travel speed, such as traffic calming measures, protect all road users.

History shows that countries that have adopted the Safe System approach implement evidence-based interventions, such as roundabouts on rural roads, and tend to have the lowest rates of fatality per population and the fastest rates of reduction in fatality numbers.[17]

Traffic calming measures save lives and reduce the severity of crash injuries, thereby reducing economic costs and positively contributing to a country’s economic growth. The economic costs related to injury and loss of life from traffic crashes include money needed to treat injuries, loss of hours worked, vehicle repair costs, insurance or third-party costs, and costs caused by increased congestion when a crash occurs.

Traffic calming can reduce crashes, injuries, and fatalities by 40%, which amount to monetary savings of 10.7 US cents per vehicle mile (1.61 km) driven on local roads, 6.6 US cents per vehicle mile on collector roads, and 7.0 US cents per vehicle mile on minor arterial roads in the United States of America (US).[18]

A World Bank study highlighted that halving road crash deaths and injuries could generate additional flows of income, with increases in GDP per capita over 24 years as large as 7.1% in Tanzania, 7.2% in the Philippines, 14% in India, 15% in China, and 22.2% in Thailand.[19]

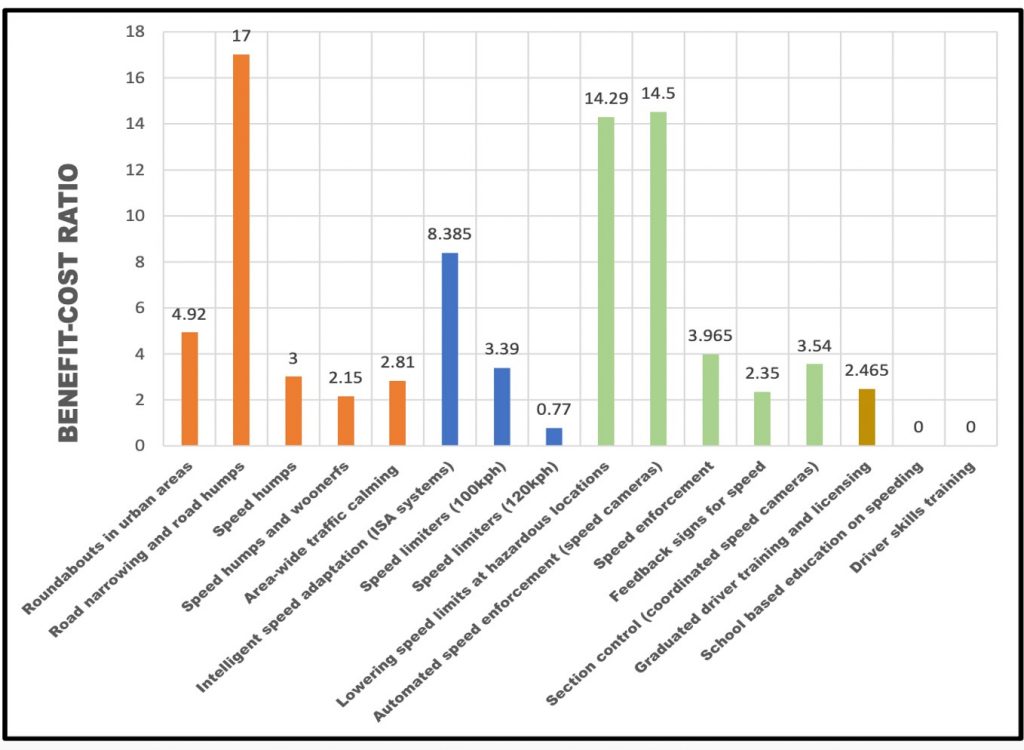

Traffic calming measures are one of the most cost-effective speed management interventions achieving benefit-cost ratios (BCRs) ranging between 2.15 and 17 depending on the type of traffic calming measure (Figure 1) i.e., every US$1 spent on traffic calming interventions reaps between a US$2.15 and US$17 benefit.

Traffic calming measures produce bigger safety benefits when implemented across a network of streets rather than one section of the road.[21]

These benefits are more significant in low- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries.[22] For example, implementing area-wide traffic calming in Mombasa in Kenya, Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, and Kampala in Uganda would yield BCRs of 17.56[23], 36.51[24] and 30[25] respectively, whereas in towns in Ireland and Greece, BCRs are in the range of 1.9–3.68[26].

Traffic calming measures make streets safer and more inviting for pedestrians and cyclists which increases access to shopping areas, boosts retail spending, improves the local economy, and may improve real estate value (e.g., by 13%).[27]

When the Mission District of San Francisco, US, implemented street designs with narrower lanes which slowed down traffic, nearly 60% of retailers reported increased spending by local people, and nearly 40% reported an overall increase in sales.[28]

The resultant speed reduction from traffic calming, for instance from 50 km/h to 30 km/h, can reduce noise levels by as much as five decibels.[29]

Traffic calming measures, such as lane narrowing, reduce the amount of land devoted to vehicular traffic and parking; the resultant extra space can be used as green areas for community activities, safer, more convenient and comfortable walking and cycling space, and for public transport.[30] This results in friendlier and more livable public streets that encourage community interaction and attract customers to commercial areas.[31] Improved walkability and bikeability also mean people are more likely to walk or cycle instead of driving.[32] This contributes to a reduction in air pollution and improvement in environmental attractiveness.[33]

Neighborhoods that make it more difficult to travel at higher speeds because of traffic calming measures, such as narrow streets and chicanes, or which have few straight thoroughfares, have significantly less crime than those without traffic calming measures.[34] A study in Dayton, Ohio, US, showed that traffic calming reduced neighborhood crime by as much as 50%.[35]

In Dar es Salaam, the School Area Road Safety Assessment and Improvements (SARSAI) program implemented low-cost infrastructure interventions in nine school environments, including concrete speed humps, rumble strips, thermoplastic pedestrian footpaths, pedestrian crossings, installation of bollards, and new signs, which reduced road injuries among children. A 12-month post-intervention evaluation showed a 26% decrease in road traffic injuries and traffic speeds in school zones reduced by up to 60%.[36]

Based on crash data between 1998 and 2000, loss of control with excessive vehicle speeds was the primary contributing factor of crashes and the majority of road users injured by these crashes were pedestrians. Low-cost traffic calming measures, such as rumble strips and speed humps, were implemented on Ghanaian roads. Rumble strips installed at the Suhum Junction on the main Accra-Kumasi highway reduced crashes by about 35% and fatalities by about 55%.[37]

Raised intersections, raised pedestrian crossings, and midblock platforms on urban arterials in Australia have resulted in a 55% reduction in casualties at raised intersections, 63% reduction at raised pedestrian crossings, and 47% reduction at midblock platforms.[38]

Rural-urban gateway treatments at 102 sites in New Zealand led to a 26% reduction in all crashes and a 23% reduction in fatal and serious crashes. The results showed that gateways, particularly with lane narrowing, were effective in lowering crashes in rural-urban transition zones.[39]

In Auckland, in 2020, a stop sign controlled busy intersection was replaced by a new raised roundabout with four pedestrian crossings. This resulted in a reduction in reported crashes at the junction, from 54 crashes over five years prior to implementation of the roundabout, to zero crashes in the 18 months afterwards. The crash cost savings from the construction of the raised roundabout and crossings were estimated to be worth more than US$6 million at a Present Value (the current value of a future sum of money based on a specific rate of return), and also encouraged modal shift, improved access to public transportation and local businesses, and helped reduce carbon emissions.[40]

In the Flemish area of Belgium, 95 roundabouts were built between 1994 and 1999. These roundabouts were built on roads with a speed limit range of 50 km/h to 90 km/h. This resulted in a 30% reduction in slight injuries, 38% reduction in serious injury crashes, and 34% reduction in overall crashes. The reduction in injuries was greater in the 90 km/h speed limit roads (59%) than the 50 km/h speed limit roads (15%).[41]

In the UK, between 1991 and 1997, traffic calming interventions were introduced in 56 villages of varying size, traffic volume, and speed limits. The traffic calming included chicanes, mini-roundabouts, speed humps, and lane narrowing in the village and/or at the gateways. This resulted in a reduction of 25% in all crashes and 50% in death and serious injury crashes across all these villages.[42]

Oslo made one lane for cars in each direction by replacing car lanes with bus or bike lanes, and installed around 500 speed humps and lower speed limits, resulting in almost two-thirds of the city’s network having a speed limit of 30 km/h. Since then, Oslo achieved zero pedestrian and cyclist fatalities in 2019.[43]

In Catania province, three traffic calming measures—speed tables, a chicane, and road narrowing—were implemented on three different road sections respectively. A before-after analysis of fatal and injury crash data on the road sections where speed tables were placed showed that the number of crashes decreased by about 44%. This included a 100% reduction in fatalities and a 38% reduction in injuries. On the section with the chicane, there was a 36% reduction in crashes, a 50% reduction in injuries and a 100% reduction in fatalities. On the sections with road narrowing, crashes were reduced by 33%, and a 32% decrease in injuries was reported.[44]

In Seattle, there were over 54,000 road traffic crashes between 2007 and 2010 and 42% of fatal crashes were attributed to speed. This prompted the Seattle Department of Transportation to set a goal of zero road fatalities by 2030 in its 2012 Road Safety Action Plan. Speed reduction was one of the priority areas to reach that goal. Changes to road environments were made by implementing traffic calming measures such as lane narrowing and speed humps. These resulted in a 29% decrease in all traffic fatalities and about 55% decrease in pedestrian fatalities. It has also led to improved walking and biking conditions, including the creation of neighborhood greenways, and 129 miles of bike lanes and sharrows (shared lane markings), improved pedestrian infrastructure, and safety improvements in walking routes to schools.[45]

At the request of residents, speed humps were built in Taunton Terrace in Auckland. After a year, an evaluation showed that the speed hump had reduced the maximum speed by 11 km/h from the 50 km/h posted speed limit and the average speed was reported to be 31.6 km/h. Similarly, the average speeds between the 14 speed humps in Blackburn Local Area Traffic Management in Hamilton decreased by an average of 6.6 km/h (-14.4%) six months after installation.[46]

After the installation of five raised platforms in Konene Street, Rotorua, the average speed between the platforms varied between 34.5 and 36.6 km/h, below the 50 km/h posted speed limit. The installation of seven raised platforms in Tuckers Road, Christchurch, resulted in a reduction of average speeds by 8.8 km/h (-17.1%).[47]

In Christchurch, a lane narrowing was implemented on a 440m section of Thorrington Road. After two years, traffic volume decreased by approximately 65%, the average speed decreased by approximately 5 km/h (-11.4%), and no crashes have been reported since the implementation.[48]

Three years after the construction of three roundabouts on Puriri Street in Butt City, the average speed reduced by 12.2 km/h (-22.7%).[49]

*Any travel speed reduction achieved via traffic calming measures has death and injury reduction benefits. In principle, a 1% reduction in average speed results in an approximate 2% decrease in injury crash frequency, a 3% decrease in severe crash frequency, and a 4% decrease in fatal crash frequency[50]. Furthermore, 10 km/h reduction in a speed limit could be expected to produce around a 15–20% reduction in injury crashes, and up to around a 40% reduction in pedestrian fatal and serious injuries.[51]

The following guidance documents can support governments in the design and implementation of traffic calming measures:

Implementing traffic calming measures achieves, supports, and/or promotes the implementation of:

Page 11, box 1, point 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7: Multimodal transport and land-use planning

Page 12, box 2, points 1,2,3,4,5,6,7: Safe road infrastructure

Page 15, box 4, points 1, 3, 4: Safe Road Use

Global Road Safety Performance Targets

Page 3:

Page 4:

Academic Expert Group of the 3rd Ministerial Conference on Global Road Safety

Recommendation 1: Page 7 and 28: “SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES AND REPORTING: including road safety interventions across sectors as part of SDG contributions.”

“In order to ensure the sustainability of businesses and enterprises of all sizes, and contribute to achievement of a range of Sustainable Development Goals including those concerning climate, health, and equity, we recommend that these organizations provide annual public sustainability reports including road safety disclosures, and that these organizations require the highest level of road safety according to Safe System principles in their internal practices, in policies concerning the health and safety of their employees, and in the processes and policies of the full range of suppliers, distributors and partners throughout their value chain or production and distribution system.“

Recommendation 2: Page 7 and 34: “PROCUREMENT: utilizing the buying power of public and private organizations across their value chains.

“In order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals addressing road safety, health,

climate, equity and education, we recommend that all tiers of government and the private sector prioritize road safety following a Safe System approach in all decisions, including the specification of safety in their procurement of fleet vehicles and transport services, in requirements for safety in road infrastructure investments, and in policies that incentivize safe operation of public transit and commercial vehicles.“

Recommendation 3: Page 7 and 37: “MODAL SHIFT: moving from personal motor vehicles toward safer and more active forms of mobility.

“In order to achieve sustainability in global safety, health and environment, we recommend that nations and cities use urban and transport planning along with mobility policies to shift travel toward cleaner, safer and affordable modes incorporating higher levels of physical activity such as walking, bicycling and use of public transit.“

Recommendation 4: Page 7 and 41: CHILD AND YOUTH HEALTH: encouraging active mobility by building safer roads and walkways.

“In order to protect the lives, security and well-being of children and youth and ensure the education and sustainability of future generations, we recommend that cities, road authorities and citizens examine the routes frequently traveled by children to attend school and for other purposes, identify needs, including changes that encourage active modes such as walking and cycling, and incorporate Safe System principles to eliminate risks along these routes.“

Recommendation 5: Page 7 and 44: INFRASTRUCTURE: realizing the value of Safe System design as quickly as possible.

“In order to realize the benefits that roads designed according to the Safe System approach will bring to a broad range of Sustainable Development Goals as quickly

and thoroughly as possible, we recommend that governments and all road authorities

allocate sufficient resources to upgrade existing road infrastructure to incorporate Safe System principles as soon as feasible.”

Recommendation 7: Page 7 and 52: ZERO SPEEDING: protecting road users from crash forces beyond the limits of human injury tolerance.

“In order to achieve widespread benefits to safety, health, equity, climate and quality of life, we recommend that businesses, governments and other fleet owners practice a zero-tolerance approach to speeding and that they collaborate with supporters of a range of Sustainable Development Goals on policies and practices to reduce speeds to levels that are consistent with Safe System principles using the full range of vehicle, infrastructure, and enforcement interventions.“

Recommendation 8: Page 7 and 56: 30 KM/H: mandating a 30 km/h speed limit in urban areas to prevent serious injuries and deaths to vulnerable road users when human errors occur.

“In order to protect vulnerable road users and achieve sustainability goals addressing

livable cities, health and security, we recommend that a maximum road travel speed limit of 30 km/h be mandated in urban areas unless strong evidence exists that higher speeds are safe.“

Recommendation 9: Page 7 and 59: TECHNOLOGY: bringing the benefits of safer vehicles and infrastructure to lowand middle-income countries.

“In order to quickly and equitably realize the potential benefits of emerging technologies to road safety, including, but not limited to, sensory devices, connectivity methods and artificial intelligence, we recommend that corporations and governments incentivize the development, application and deployment of existing and future technologies to improve all aspects of road safety from crash prevention to emergency response and trauma care, with special attention given to the safety needs and social, economic and environmental conditions of low- and middle-income nations.“

Page 14: Speed management

“Establish and enforce speed limit laws nationwide, locally and in cities

Build or modify roads which calm traffic, e.g. roundabouts, road narrowing, speed bumps, chicanes and rumble strips

Require car makers to install new technologies, such as intelligent speed adaptation, to help drivers keep to speed limits”

Page 14: Leadership on road safety

“Create an agency to spearhead road safety

Develop and fund a road safety strategy

Evaluate the impact of road safety strategies

Monitor road safety by strengthening data systems

Raise awareness and public support through education and campaigns”

Page 14: Infrastructure design and improvement

“Provide safe infrastructure for all road users including sidewalks, safe crossings, refuges, overpasses and underpasses

Put in place bicycle and motorcycle lanes

Make the sides of roads safer by using clear zones, collapsible structures or barriers

Design safer intersections

Separate access roads from through-roads

Prioritize people by putting in place vehicle-free zones

Restrict traffic and speed in residential, commercial and school zones

Provide better, safer routes for public transport”

Page 3-5:

“1. Drive the implementation of the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030, which describes key suggested actions to achieve the reduction in road traffic deaths of at least 50 per cent by 2030 and calls for setting national targets to reduce fatalities and serious injuries for all road users with special attention given to the safety needs of those road users who are the most vulnerable to road-related crashes, including pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists and users of public transport, taking into account national circumstances, policies and strategies;

2. Develop and implement regional, national and subnational plans that may include road safety targets or other evidence-based indicators where they have been set, and put in place evidence-based implementation processes by adopting a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach and designating national focal points for road safety with the establishment of their networks in order to facilitate cooperation with the World Health Organization to track progress towards the implementation of the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030;

3. Promote systematic engagement with relevant stakeholders, including from transport, health, education, finance, environmental and infrastructure areas, and encourage Member States to consider becoming contracting parties to the United Nations legal instruments6 on road safety and, beyond accession, applying, implementing and promoting their provisions or safety regulations;

4. Implement a Safe System approach through policies that foster safe urban and rural road infrastructure design and engineering; set safe adequate speed limits supported by appropriate speed management measures; enable multimodal transport and active mobility; establish, where possible, an optimal mix of motorized and non-motorized transport, with particular emphasis on public transport, walking and cycling, including bike-sharing services, safe pedestrian infrastructure and level crossings, especially in urban areas;

5. Adopt evidence- and/or science-based good practices for addressing key risk factors, including the non-use of seat belts, child restraints and helmets, medical conditions and medicines that affect safe driving, driving under the influence of alcohol, narcotic drugs and psychotropic and psychoactive substances, inappropriate use of mobile phones and other electronic devices, including texting while driving, speeding, driving in low visibility conditions, driver fatigue, as well as the lack of appropriate infrastructure; and for enforcement efforts, including road policing, coupled with awareness and education initiatives, supported by infrastructure designs that are intuitive and favour compliance with legislation and a robust emergency response and post-crash care system;

6. Ensure that road infrastructure improvements and investments are guided by an integrated road safety approach that, inter alia, takes into account the connections between road safety and eradication of poverty in all its dimensions, physical health, including visual impairment and mental health issues, the achievement of universal health coverage, economic growth, quality education, reducing inequalities within and among countries, gender equality and women’s empowerment, decent work, sustainable cities, environment and climate change, as well as the broader social determinants of road safety and the interdependence between Sustainable Development Goals and targets that are integrated, interlinked and indivisible, and assures minimum safety performance standards for all road users;

9. Integrate a gender perspective into all policymaking and implementation of transport policies that provide for safe, secure, inclusive, accessible, reliable and sustainable mobility, and non-discriminatory participation in transport; and ensure that policies cater to road users who might be in vulnerable situations, in particular children, youth, older persons and persons with disabilities;

10. Deliver evidence-based road safety knowledge and awareness programmes to promote a culture of safety among all road users and to address high-risk behaviours, especially among youth, and the broader road-using community through advocacy, training and education and encourage private sector participation in supplementing national efforts in promoting greater road safety awareness as part of corporate social responsibility;

12. Acknowledge the importance of adequate, predictable, sustainable and timely international financing without conditionalities in complementing the efforts of countries in mobilizing resources domestically, especially in low- and middle-income countries; support the demands of financing in developing countries by leveraging the United Nations Road Safety Fund and other dedicated mechanisms, as appropriate, for promoting safe road transport infrastructure and for supporting the implementation of measures required to meet the voluntary global performance targets, including by supporting the voluntary replenishment of all United Nations system road safety funds and mechanisms;

13. Promote capacity-building, knowledge-sharing, technical support and technology transfer programmes and initiatives on mutually agreed terms in the area of road safety, especially in developing countries, which confront unique challenges and, where possible, the integration of such programmes and initiatives into sustainable development assistance programmes through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation formats, as well as public-private collaboration;

14. Promote the development, knowledge-sharing and deployment of vehicle automation and new technologies in traffic management using both intelligent transport systems and cooperative intelligent transport systems, in line with national requirements, to improve accessibility and all aspects of road safety while also monitoring, assessing, managing and mitigating challenges associated with rapid technological change and increasing connectivity;

15. Contribute to international and national road safety by encouraging research and improving and harmonizing disaggregated data collection on road safety, including data on road traffic crashes, resulting deaths and injuries, and road infrastructure, including those gathered from regional road safety observatories, to better inform policies and actions; strengthen road safety data capacity, including in low- and middle-income countries, and improve the quality of systematic and consolidated data collection and comparability at the international level for effective and evidence-based policymaking and implementation while taking into account privacy and national security considerations; and request the World Health Organization to continue to monitor and report on progress towards the achievement of the goals of the decade of action;

16. Leverage the full potential of the multilateral system, in particular the World Health Organization, the good offices of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Road Safety, the United Nations regional commissions and relevant United Nations entities, as well as other stakeholders, including the Global Road Safety Partnership, to support Member States with dedicated technical assistance and, upon their request, in applying voluntary global performance targets for road safety when appropriate;

[1] Our definition is based on the following sources:

[2]World Health Organization. (2021). Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030

[3] International Road Assessment Programme, iRAP. (2022). The Road Safety Toolkit.

[4] United States Department of Transportation. (2014). Engineering Speed Management Countermeasures: A Desktop Reference of Potential Effectiveness in Reducing Speed. Federal Highway Administration.

[5] Poswayo, A., Witte, J., & Kalolo, S. (2017). SARSAI : Low Cost Speed Management Interventions around Schools – Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Road Safety Case Studies. Journal of the Australian College of Road Safety, 28(3), 63–68.

[6] Makwasha, T. & Turner, B. (2013). Evaluating the Use of Rural-Urban Gateway Treatments in New Zealand. Proceedings of the 2013 Australasian Road Safety Research, Policing & Education Conference 28–30 August, Brisbane, Queensland.

[7] Harvey, T. (1992). A review of current traffic calming techniques. Primavera, V2016/31102.

[8] Damsere-Derry, J., Ebel, B.E., Mock, C.N., Afukaar, F., Donkor, P., & Kolawole, T.O. (2019). Evaluation of the effectiveness of traffic calming measures on vehicle speeds and pedestrian injury severity in Ghana. Traffic Injury Prevention, 20:3, 336-342.

[9] P99 & 100, Sharpin, A.B., Adriazola-Steil, C., Luke, N., Job, S., Obelheiro, M., Bhatt, A., Liu, D., Imamoglu, T., Welle, B., & Lleras, N. (2021). Low-Speed Zone Guide. Bloomberg Philanthropies.

[10] Afukaar F.K. (2003). Speed control in developing countries: issues, challenges and opportunities in reducing road traffic injuries. Injury control and safety promotion, 10(1-2), 77–81.

[11] Global Road Safety Facility. (2023). Speed Management Hub – Frequently Asked Questions, Note 8.2.

[12] National Association of City Transportation Officials. (2013). Urban Street Design Guide. Island Press.

[13] Bellefleur, O. & Gagnon, F. (2011). Urban Traffic Calming and Health. National Collaborating Center for Healthy Public Policy.

[14] Turner, B., Job, S., & Mitra, S. (2021). Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work. World Bank, Washington, DC., USA.

[15] World Road Association. (2019). The Safe System Approach – Road Safety Manual: A Manual for Practitioners and Decision-Makers on Implementing Safe System Infrastructure.

[16] International Transport Forum. (2008), Towards Zero: Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[17] https://www.wri.org/research/sustainable-and-safe-vision-and-guidance-zero-road-deaths.

[18] Litman, T. (1999). Traffic Calming Benefits, Costs and Equity Impacts. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

[19] World Bank. (2017). The High Toll of Traffic Injuries: Unacceptable and Preventable. World Bank.

[20] Job, R.F.S. & Mbugua, L.W. (2020). Road Crash Trauma, Climate Change, Pollution and the Total Costs of Speed: Six graphs that tell the story. GRSF Note 2020.1. Washington DC: Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank.

[21] International Road Assessment Programme, iRAP. (2022). The Road Safety Toolkit.

[22] Job, R.F.S. & Mbugua, L.W. (2020). Road Crash Trauma, Climate Change, Pollution and the Total Costs of Speed: Six graphs that tell the story. GRSF Note 2020.1. Washington DC: Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank.

[23] Mohapatra, D.R. (2017). An Economic Evaluation of Feasibility of Non-Motorized Transport Facilities in Mombasa Town of Kenya. In Economic and Financial Analysis of Infrastructure Projects, an Edited Volume (pp 134-157). New Delhi, India: Educreation Publishing.

[24] Mohapatra, D.R. (2017). Feasibility of Non-Motorized Transport Facilities in Addis Ababa City of Ethiopia: An Economic Analysis. In Economic and Financial Analysis of Infrastructure Projects, an Edited Volume (pp 184-204). New Delhi, India: Educreation Publishing.

[25] United Nations Economic Commission for Africa & United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2018). Road safety performance review Uganda. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

[26] Yannis, G., Evgenikos, P., & Papadimitriou, E. (2008). Best practice for cost-effective road safety infrastructure investments. CEDR, Paris.

[27] Sharpin, A.B., Banerjee, S.R., Adriazola-Steil, C., & Welle, B. (2017). The Need for (Safe) Speed: 4 Surprising Ways Slower Driving Creates Better Cities. World Resources Institute.

[28] Sharpin, A.B., Banerjee, S.R., Adriazola-Steil, C., & Welle, B. (2017). The Need for (Safe) Speed: 4 Surprising Ways Slower Driving Creates Better Cities. World Resources Institute.

[29] 20’s Plenty for Us. (2016). 20mph Cuts Air & Noise Pollution to Prevent Blighted Lives. A 20’s Plenty for Us Briefing.

[30] Litman, T. (1999). Traffic Calming Benefits, Costs and Equity Impacts. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

[31] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Global Street Design. Island Press; 2nd None ed. edition.

[32] Sharpin, A.B., Banerjee, S.R., Adriazola-Steil, C., & Welle, B. (2017). The Need for (Safe) Speed: 4 Surprising Ways Slower Driving Creates Better Cities. World Resources Institute.

[33] Rossi I.A., Vienneau D., Ragettli M.S., Flückiger B., & Röösli M. (2020). Estimating the health benefits associated with a speed limit reduction to thirty kilometres per hour: A health impact assessment of noise and road traffic crashes for the Swiss city of Lausanne. Environ Int.;145:106126.

[34] Lockwood, I.M. & Stillings, T. (1988). Traffic calming for crime reduction and neighborhood revitalization. 68th Annual Meeting of the Institute of Transportation Engineers.

[35] Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center. (2007). Traffic Calming and Crime Prevention. PBIC Case Study—Ohio, Florida & Virginia.

[36] Poswayo, A., Kalolo, S., Rabonovitz, K., Witte, J., & Guerrero, A. School Area Road Safety Assessment and Improvements (SARSAI) programme reduces road traffic injuries among children in Tanzania. (2019). doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042786. Epub 2018 May 19. PMID: 29778992.

[37] Afukaar, F.K. (2003). Speed control in developing countries: issues, challenges and opportunities in reducing road traffic injuries. Injury control and safety promotion, 10(1-2), 77–81.

[38] P. 20-27, Makwasha, T. & Turner, B. (2017), ‘Safety of raised platforms on urban roads’, Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety, vol. 28.

[39] P. 14-20, Makwasha, T. & Turner, B. (2013). Evaluating the use of rural-urban gateway treatments in New Zealand. Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety, 24(4).

[40] Royce, B. (2022). “Fix Crash Corner’ – A Roundabout Story” Journal of Road Safety, 33(4), 61-67.

[41] De Brabander, B., Nuyts, E., & Vereeck, L. (2005). Road safety effects of roundabouts in Flanders. Journal of Safety Research, 36(3), 289–296.

[42] Wheeler, A.H. & Taylor, M.C. (2000). Changes in accident frequency following the introduction of traffic calming in villages Prepared for Charging and Local Transport Division, Transport Research Laboratory, TRL REPORT 452.

[43] Hartmann, A. & Abel, S. (2020). How Oslo Achieved Zero Pedestrian and Bicycle Fatalities, and How Others Can Apply What Worked. World Resources Institute.

[44] Distefano N. & Leonardi S. (2019). Evaluation of the Benefits of Traffic Calming on Vehicle Speed Reduction. Civil Engineering and Architecture 7(4): 200-214.

[45] Health Resources in Action. (2013). Seattle, Washington: A Multi-Faceted Approach To Speed Reduction. A Community Speed Reduction Case Study.

[46] P. 77-78, 81-82, Minnema, R. (2006). The Evaluation Of The Effectiveness Of Traffic Calming Devices In Reducing Speeds On “Local” Urban Roads In New Zealand. February.

[47] P. 87-91, Minnema, R. (2006). The Evaluation Of The Effectiveness Of Traffic Calming Devices In Reducing Speeds On “Local” Urban Roads In New Zealand. February.

[48] P. 107-108, Minnema, R. (2006). The Evaluation Of The Effectiveness Of Traffic Calming Devices In Reducing Speeds On “Local” Urban Roads In New Zealand. February.

[49] P. 115-116, Minnema, R. (2006). The Evaluation Of The Effectiveness Of Traffic Calming Devices In Reducing Speeds On “Local” Urban Roads In New Zealand. February.

[50] OECD/International Transport Forum. (2018). Speed and crash risk. ITF (International Transport Forum).

[51] Turner, B., Job, S., & Mitra, S. (2021). Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work. World Bank, Washington, DC., USA.

[52] Sharpin, A.B., Adriazola-Steil, C., Job, S., et al. (2021). Low-Speed Zone Guide. World Resources Institute and The Global Road Safety Facility.

[53] Global Designing Cities Initiative. (2016). Global Street Design. Island Press; 2nd None ed. edition.

[54] International Road Assessment Programme, iRAP. (2022). The Road Safety Toolkit.